Text plays a crucial role in the work of Brooklyn-born artist Jean-Michel Basquiat, often overwhelming visual aspects with a mass of black scribbles. From his initial work as a graffiti artist in Lower Manhattan with which he announced his creative voice as SAMO©, Basquiat engaged in a discourse on race, wealth, and art in America. Had his whirlwind life been slightly different, Basquiat may well have achieved fame as a poet.

Given the importance of text to Basquiat’s work, it should come as no surprise that he kept copious notes. He preferred cheap, marble composition books, some of which you can now see on display at the Brooklyn Museum in a new exhibition “Basquiat: The Unknown Notebooks,” or as the exhibition’s synopsis puts it “#basquiatnotebooks.” While this much hyped exhibit offers the opportunity to see Basquiat’s famous textual artistry on a smaller, more concentrated scale, the exhibition’s mixed messages could lead some visitors astray.

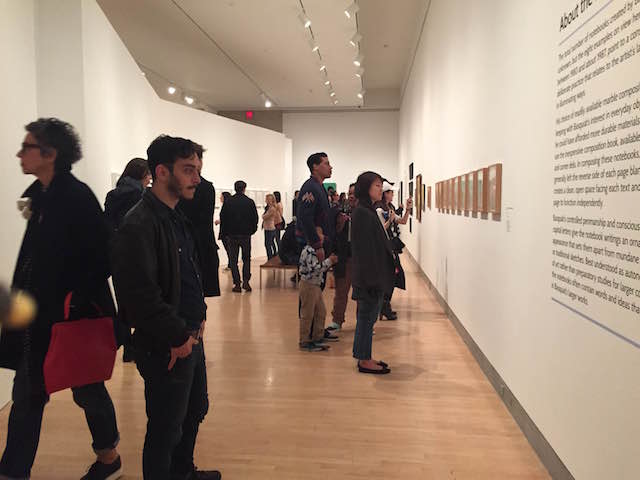

On the first Saturday since the exhibition opened, the museum was crowded with visitors taking advantage of the free admission. “Salt Peanuts” played energetically in the lobby, but as the elevator emptied nearly every visitor into the popular Basquiat exhibition, a different musical tone took over. A film starring Basquiat called “Downtown 81” played near the entrance of “The Unknown Notebooks,” spilling out the ethereal noises of Gray, Basquiat’s own band (formed on a whim without musical training). The music announced a chaotic scene.

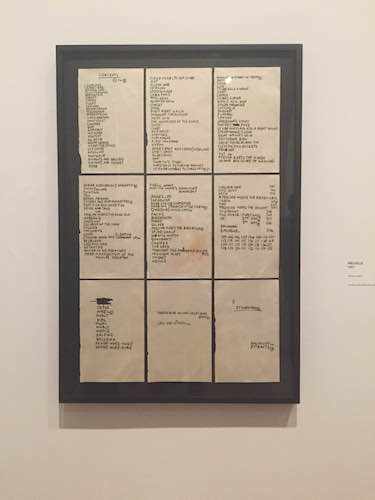

The exhibition comprises a single room. Pages from deconstructed notebooks, which Basquiat kept from 1980 to 1987, are presented in long cases along walls or hung individually. While Basquiat’s overtly arranged and readable text suggests the notes were meant for display, there’s something unnerving about seeing the dismembered notebooks laid out with the carcasses of the notebook covers displayed as sculptures nearby. But given Basquiat’s irreverence for the sanctity of his finished works – he would often leave sneaker prints on the pieces scattered across his apartment floor – he’d likely ok such presentation.

The room is broken up by several jagged freestanding walls, which provide little guidance and cause foot traffic to dart chaotically. One couple enters the room a bit stymied as to how to proceed, which seems ironic given the presence of many crude maps populating the works hanging nearby. The crowd and odd setup make it difficult to spend much time on individual pages. A few of Basquiat’s larger pieces punctuate the collection, offering visitors a chance to sit and admire a single piece, but these formal works are often displayed in New York and elsewhere, receiving the attention and acclaim they deserve. Their presence in this exhibition, however, distracts from the primary focus: the notebooks.

Therein lies the difficulty with this exhibit. Just as in the major works, Basquiat’s notebooks bear his cultural commentary and personal observations. Through the artist rage the voices of overbearing cultural iconography, nonsensical racial prejudice despite black cultural achievement, and divergent artistic lineages that inform the New York creative community. But his informal note-taking process wasn’t just practice for larger works. The notes exhibit a perfected editorial style, which is at work in the famous pieces, but which he executed just as precisely on this smaller scale.

By crossing out, pasting over, redacting, replacing and juxtaposing his commentary, the artist evoked an ongoing sociopolitical dialogue. Basquiat eschewed elitist references, so each reference in his work is simple on its own. Woven together in the larger works, the phrases create a dense interrelation that resists one settled reading and provokes further contemplation. Yet the sparse arrangement of pages in the exhibition breaks the notebooks’ juxtaposition and makes it difficult for the notes to compete for attention next to the full paintings. This arrangement undercuts the importance of the notes themselves as vehicles for social commentary. They appear simply as a behind the scenes look at later, greater works.

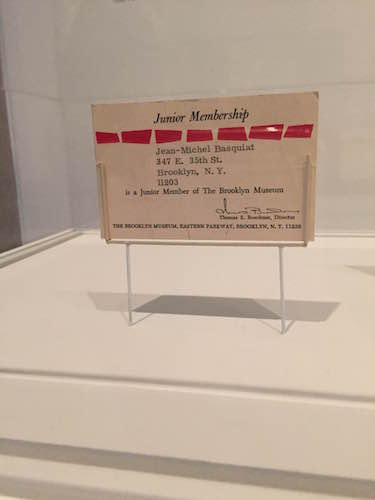

Similarly, Basquiat’s childhood membership card to the Brooklyn Museum, on display near the exhibit’s entrance, casts the works in an odd light. The card hints at the artist’s prodigious youth, but the exhibit is not, as the invocation of a preteen Basquiat might suggest, juvenalia. Rather, the notebooks on display were created concurrently with some of Basquiat’s major works and represent an artist at his prime. The membership card is also a not-so-subtle attempt by the museum to claim the artist as their own, but the gesture rings hollow when compared to legitimate declarations of Brooklynite artistic lineage with Basquiat, like street artist Eduardo Kobra’s recent Basquiat/Warhol mural in Williamsburg.

Ultimately, “Basquiat: The Unknown Notebooks” is jumbled. The exhibit’s arrangement distracts from the primary material. Maybe the notebooks could have provided more insight in an archive, where they would have remained intact, though it is difficult to argue for privatization of such deliberately accessible material. Still, Basquiat engaged issues of racism and social inequality that remain prevalent, making his exhibitions, even those as confusing as this one, a tool to elicit valuable social dialogue.

If you have yet to experience Basquiat, “The Unknown Notebooks” provides a good opportunity to see his work in his home town. If you’re a longtime fan, head to the exhibit all the same, but bypass the major works you’ve seen for the fascinating notes you haven’t. You can even pick up a marble composition notebook of your own at the gift shop on the way out.

“Basquiat: The Unknown Notebooks” runs through August 23 at the Brooklyn Museum

Leave a Reply